The global tax minimum is a lose-lose deal negotiated by the Biden Administration.

What is happening?

In October 2021, over 130 countries representing more than 90% of global GDP, agreed to impose a global minimum tax of 15% on multinational companies with annual revenue over €750 million. Starting in 2024, the law will allow countries implementing the agreement to raise taxes on foreign companies operating in their jurisdiction if they aren’t meeting the 15% minimum domestically. Starting in 2025, countries will assess foreign companies’ worldwide operations and charge more if they are below 15% anywhere —including the company’s home base. The right to tax income first belongs to the source country. If the source country doesn’t apply it, the home country of the parent company can collect the tax. Due to political disagreement and the complexity of existing tax treaties, the US Congress’s decision about the implementation is uncertain.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) created a two-pillar approach to address international tax laws. The global tax minimum represents Pillar Two, while Pillar One seeks to reallocate a portion of taxable income to market jurisdictions, expanding a country’s authority to tax profits from foreign companies. While over 130 countries agreed on adopting Pillar Two, Pillar One is facing opposition from the United States, Saudi Arabia, India, and the majority of African countries. After a G20 Summit in February 2023, the French minister reported that Pillar One “chances of success are slim.”

Pillar Two is expected to add $220 billion annually in tax income globally, equivalent to 9% of global corporate income tax revenues, according to the OECD.

What is causing it to happen?

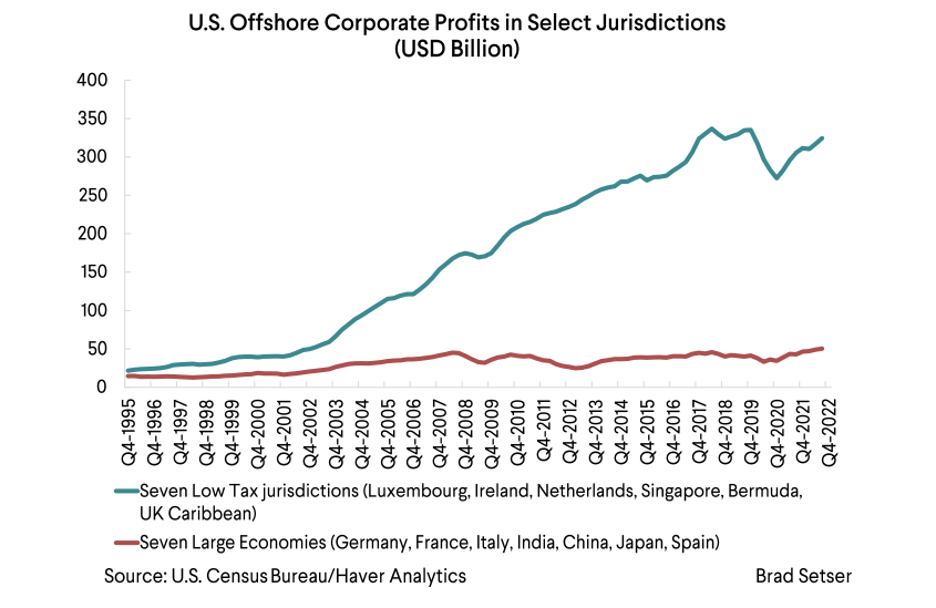

The shift towards a global tax minimum was driven by concerns over multinational corporations engaging in tax avoidance practices. The existing rules do not adequately address tax challenges brought by global digitalization, allowing corporations to legally move millions into offshore tax havens like Switzerland and the Cayman Islands. The OECD estimated that between 4-10% of global tax revenues are lost as a result of shifting profits to low-tax jurisdictions. In response, the effective rate of 15% will ensure that large corporations pay their fair share of tax anywhere they do business, regardless of their physical location. “What countries are doing is protecting their tax base,” said Jason Yen, an international tax principal at Ernst & Young.

Despite the deal being one of the signature moves by the Biden Administration, the US Congress is experiencing opposition and uncertainty to Pillar One and Two, respectively. This is because the deal targets the country’s big pharmaceutical and tech companies, potentially costing them hundreds of millions of dollars. Such companies sell products around the world and spend large amounts of money on research and development as tax strategy to benefit from the R&D Tax Credit rule.

What is likely to happen next?

The global minimum tax will apply to well more than 1,000 US corporations, a much larger group of companies than those affected by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) minimum tax law – 150. According to the nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), this is a lose-lose deal negotiated by the Biden Administration. The analysis was requested by Senate Finance Committee members and concludes that the US will lose more than $120 billion in 2025 if the global tax minimum is adopted worldwide but not domestically. On the flip side, the US would lose $56.5 billion under the administration’s preferred path forward. Technology and pharmaceutical companies are expected to take the burnt of this policy.

According to a report by the OECD, there is a growing reliance on technology for implementing the global tax minimum. The concern is that developing countries might not be able to deliver functional systems by the beginning of the next year, allowing advanced economies to make tax profits instead. The fear of losing tax proceeds will encourage developing nations to invest in the technology necessary to execute the agreement.

It is unclear how $370 billion in subsidies for clean energy industries will be treated under the new global arrangement. The US tax credits might reduce a company’s US tax liability to under the 15% minimum, potentially allowing foreign governments to add tax profit. Due to political disagreement and tax complexities, the US is unlikely to act until after the 2024 election.

Sources

- https://taxfoundation.org/global-tax-agreement/

- https://www.oecd.org/tax/international-community-strikes-a-ground-breaking-tax-deal-for-the-digital-age.htm

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/big-pharma-quietly-pushes-back-on-global-tax-deal-citing-covid-19-role-11627378146

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/big-pharma-quietly-pushes-back-on-global-tax-deal-citing-covid-19-role-11627378146

- https://www.finance.senate.gov/ranking-members-news/jct-us-stands-to-lose-revenue-under-oecd-tax-deal

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/global-tax-mess-awaits-u-s-companies-and-congress-isnt-helping-eec13f2c?mod=Searchresults_pos2&page=1

- https://www.ibfd.org/news/us-india-and-saudi-arabia-are-blocking-oecd-led-pillar-one-french-finance-minister-says

- https://www.ft.com/content/ad60e9e6-cd60-4613-9298-636e053ebb4b